guests-pit

Rediscovering Orchestra Super Mazembe

by Franscine Machinda

October 22, 2025

guests-pit

October 22, 2025

What makes an artist heroic?

Like most people in my generation, I grew up listening to Orchestra Super Mazembe not by choice, but by virtue of being around my rhumba and lingala obsessed middle-aged uncles. It was the music they’d grown up listening to, already nostalgic for them even as early as the late 1990s and early 2000s. This music soon became nostalgic for me too even as I developed my own taste; and whenever I’d hear it, I’d think of home.

When I gained interest in and started writing about Kenyan music, I revisited the band’s discography to expand my knowledge on the history of African music at large, actively listening for the first time. It was beautiful, perhaps one of my most memorable listening experiences. I could almost feel how alive they must’ve felt when they made it. Their music is undeniably some of the best ever made. And how exciting, how powerful and hopeful that this music was made right here, at home?

But first, some context.

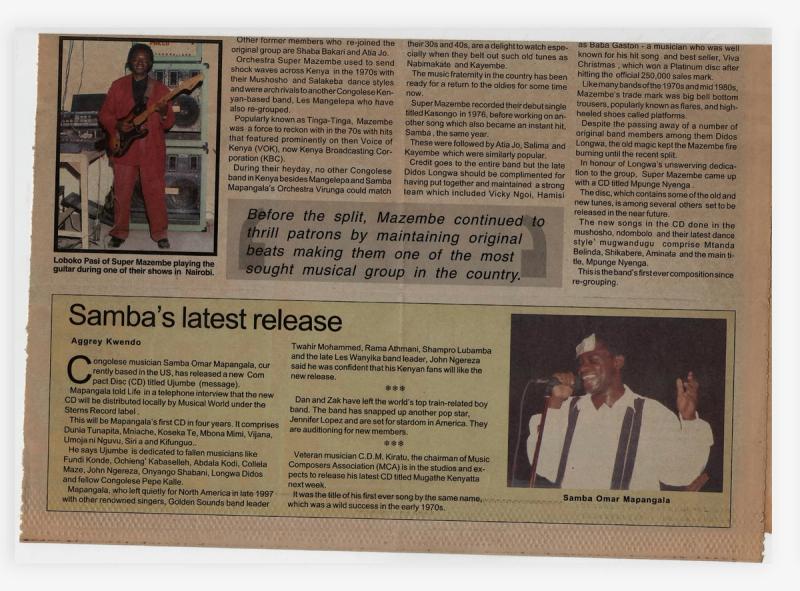

At the turn of and well into the 1970s, Nairobi, Kenya, was considered one of Africa’s most exciting and dynamic music and performing arts centres. A multinational city bursting with opportunity even then, it invited, welcomed, and nourished sounds from across the continent, with rhumba and soukous as the most well-received genres. Owing to this, like many other Congolese musicians, the members of the dance band Orchestra Super Mazembe made the daring and bold decision to relocate to the cross-cultural hub in 1974.

Initially founded and led by Longwa Didos Mutonkole as Super Vox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire) in 1967, the group had first moved to Zambia in 1969 where they played at nightclubs while exploring and shaping their musical identity and sound. It is there that they met the legendary musician Nashil Pichen who would later come to heavily influence them and speak highly of Kenya’s sprightly music scene, fueling their hasty move to the country.

While it was as vibrant a scene as had been described to them, the group found that it was also highly competitive and fast paced. Regardless, after discovering that there was another group called Super Vox working and performing in the same locale and renaming themselves to Orchestra Super Mazembe, the band got to work cumulating an audience and cementing themselves as one of East Africa’s most legendary musical acts to date.

What seemed to be one of the band’s biggest advantages in the region’s vast musical landscape was the brilliance and curiosity that the members displayed while engaging with the work, processes, and formulas of their East African and continental peers. They also often listened and responded to the audience’s desires, building a dedicated fanbase along the way. These qualities allowed them to readily receive and absorb the region’s musical output and knowledge and welcome the influence it would have on their own work, all while heavily influencing these evolving sounds and methods just the same; helping shape and define what would later be considered the region’s golden era of music.

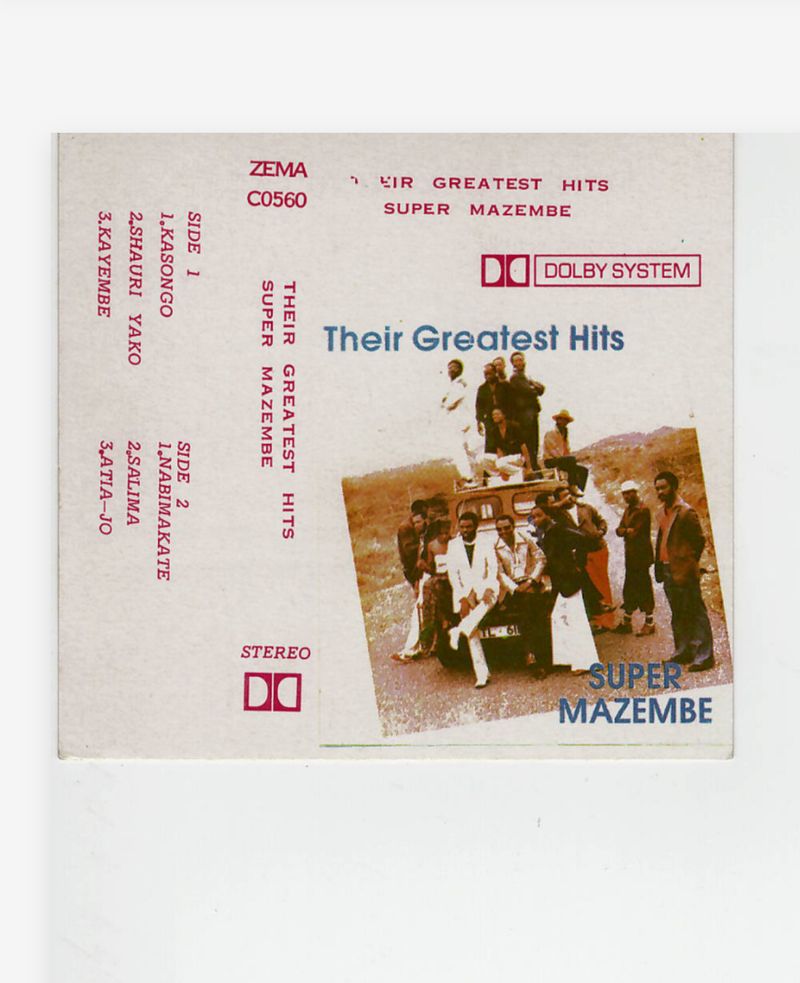

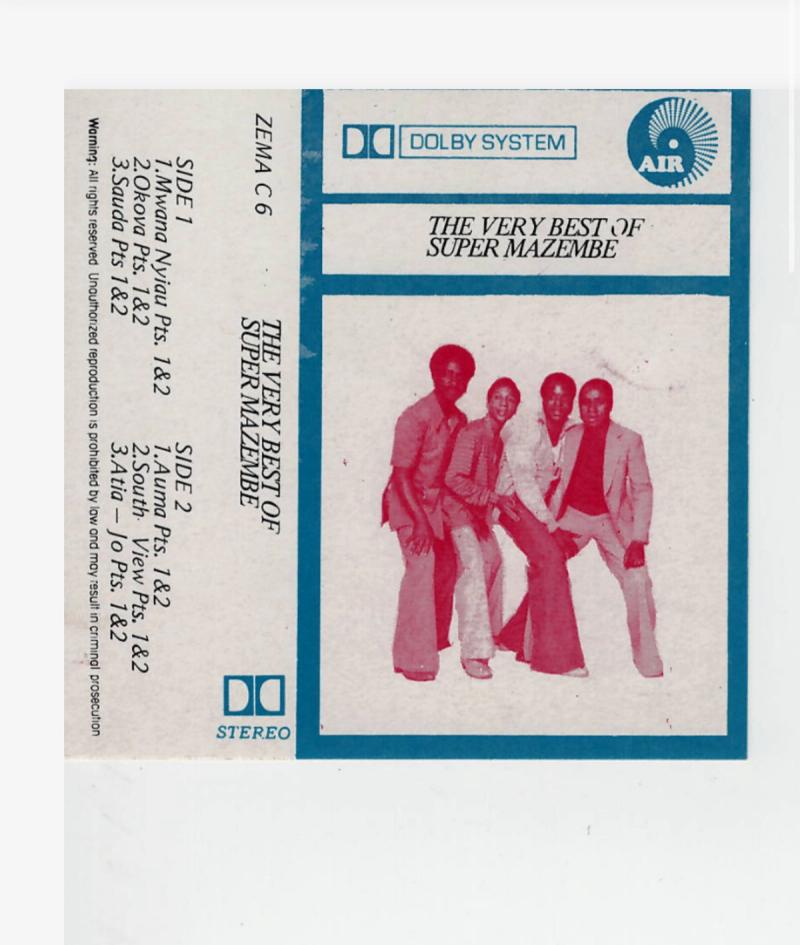

Released in 1976, “Shauri Yako”, Mazembe’s first hit single, was their rendition of a song originally performed by Nguashi Ntimbo and Festival Du Zaire. The track was received with high praise and set the band up for a few of their most successful years. What a few Kenyan youth may now consider the band’s most interesting offering, “Kassongo” came shortly after with just as much, if not more, punch. More hit singles such as “Samba”, “Jiji”, “Bwana Nipe Pesa”, as well as beloved deep cuts such as “Mama Lea” followed, with the band launching their own record label named Editions Mazembe and releasing more than forty singles by 1984.

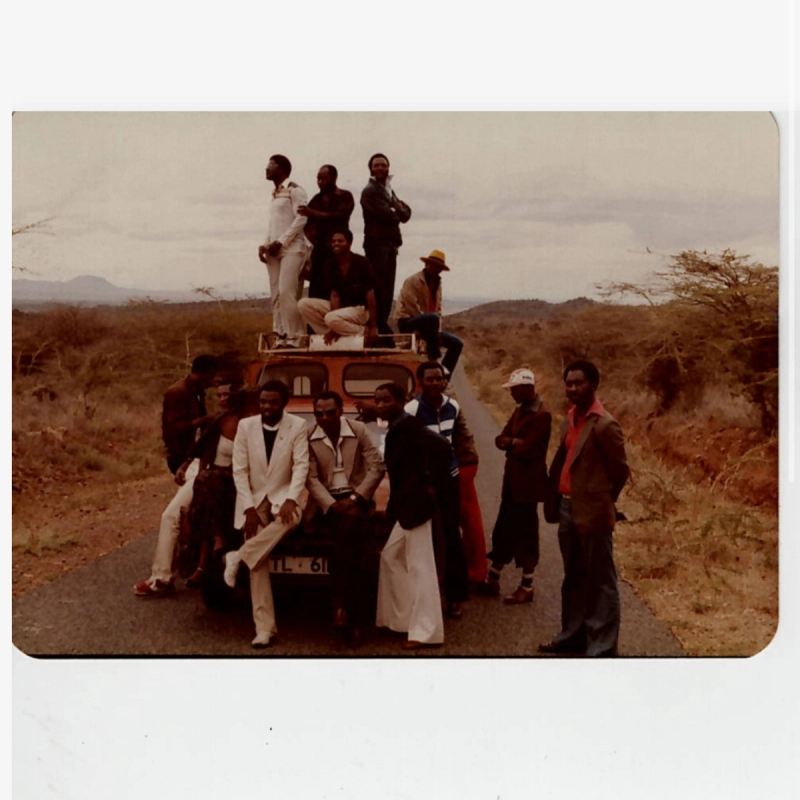

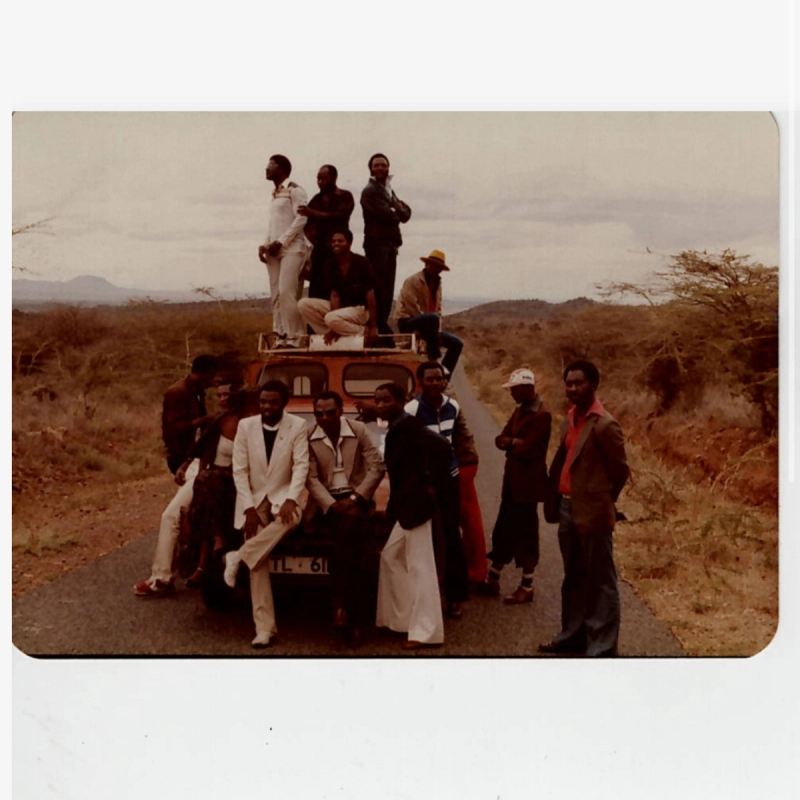

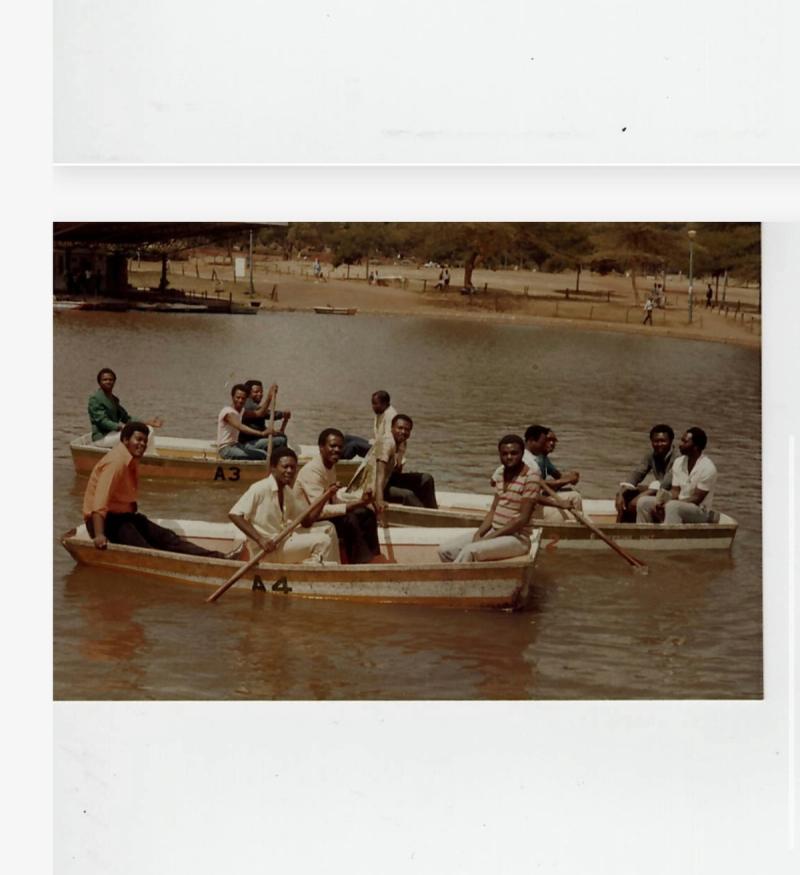

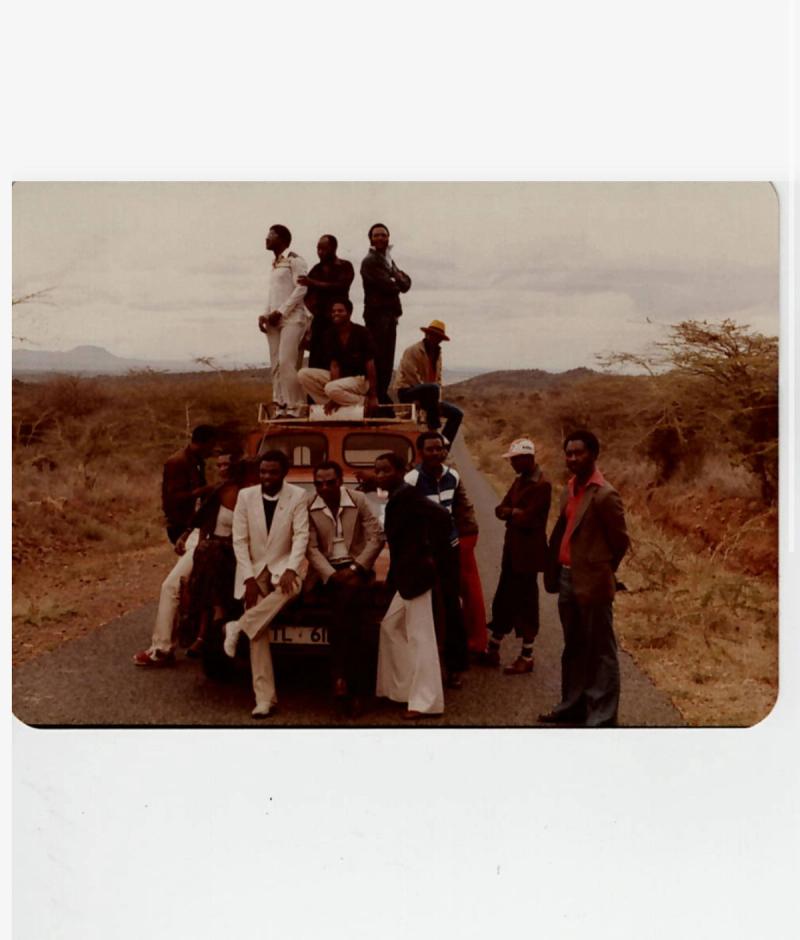

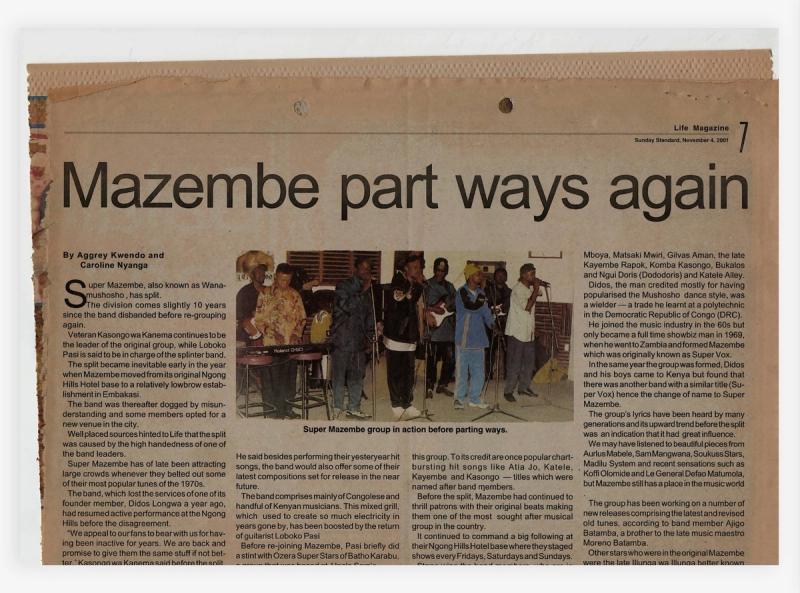

The group was known for their intense dedication and work ethic which translated into their energetic and engaging live performances. They popularised their own dance style called mushosho, connecting with their dedicated audiences even further. While mostly based in Nairobi, the free-spirited band often toured across cities and countries, refusing to be tied to specific venues and spaces. They often performed in clubs, dance halls, and on radio.

At their peak, Super Mazembe helped bridge cultural barriers, unafraid to apply different and/or new elements to their work. They allowed different contexts to shape and reshape their music where necessary and helped cultivate continental artistic identity and community. Combining their Congolese rhumba and soukous sound with Kenyan Benga, Swahili Pop, and Tanzanian rhumba, the group created a hypnotic and iconic signature sound that would influence the region’s music for decades to come, all while swinging back and forth effortlessly from Lingala to Swahili as their primary languages. Lyrically, their music tackled themes of love, travel and migration, betrayal, and politics while keeping their sound groovy and fun, accessible even, regardless of the topic.

From busy Saturday mornings spent deep cleaning to quiet Sunday afternoons spent in backyards, the group’s music was used to soundtrack everyday life at a time many remember as simpler. As with most music being made and consumed in Africa at the time, Mazembe’s work was known for its long instrumental sections, addictive melodies, layered vocals, and witty songwriting that often leaned into a comedic perspective on social and personal issues. They operated at a time where music was allowed room to breathe, especially in the genres they dabbled in. Their music crossed borders and cultures, finding homes in households across East and Central Africa where their cassette tapes and vinyl records quickly became a staple.

On influence, a few Kenyan creatives have been clear about their impact in today’s art scene. Tela Wangeci, a music journalist says, “In essence, Super Mazembe helped Kenya find its rhythm on the continental stage proving that local audiences could embrace sophistication without losing their roots. Beyond the music, they symbolized the pan-African cultural fusion that has always defined Kenya’s urban sound paving the way for later genres like benga, kapuka, and even modern Afro-fusion to draw from cross-border influences.Through timeless hits like Shauri Yako, Sango Ya Mapenzi, and Kasongo, Super Mazembe introduced polished instrumentation, multilingual lyrics (Lingala, Swahili, and English), and dynamic stage presence that set new standards for Kenyan bands. Their success inspired a generation of Kenyan musicians to professionalize their craft, tour regionally, and think beyond local markets.”

Thulani, a budding indie musician says, “I personally feel that a lot of African music, especially from East Africa, is heavily influenced by early rhumba styles like the music Super Mazembe pioneered. Without such an influence, it's hard to imagine what kind of identity Kenyan music would assume - but because of them, their influence acts as a bridge between the music that was loved back then and the music that defines our culture today.”

And Mr. LU*, a producer, DJ, and rapper who often reworks older Kenyan music, says, “I sample East African art, songs and musical histories to honor the artists who came before me, weaving their work into mine as a form of collaboration across time. I see sampling as a way to introduce younger audiences to the music and stories of generations that came before us, not just a fusion of new and old sounds to arrive at a musical composition.“

Super Mazembe’s line-up consisted of Mutonkole Longwa Didos, Kassonga Was Kanema, Katele Aley, Loboko Bua Mangala, Lovy Longomba, Mwanza Wa Mwanza Mulunguluke, Nashil Pichen Kazembe, and Ngoi Kitenge Was Kitombole. Older archived documents also list Bukasa Wa Bukasa, Kayembe Miketo Tshibambe, and Komba Kassongo as members of the band by June 1979, joined by Humphrey Achuo, Mike Ogutu Ayieye, and Silas Kamau by February 1980. Members cited East African, Lingala, Cuban and Latin, pan-african, and continental sounds as some of their biggest influences, often mentioning Franco Luambo Makiadi, Tabu Ley Rochereau, Miriam Makeba, Fela Kuti, Daudi Kabaka, Les Wanjika, among others, as the key artists that shaped their work.

Due to economic and political changes, a shift in popular music taste and demand, and the passage of time, the legendary group disbanded in 1985. Four decades later, their work is still as hypnotic as it was then (if not more, as it ages beautifully). It is still culturally rich, melodic, and restless, still some of the most invigorating, exciting, and experimental music ever produced, and still accessible and familiar. It is still timeless; still makes the continent feel alive.

Super Mazembe’s legacy and influence are inescapable. Their music is still widely known, revered, and celebrated for both its brilliance and its historical and cultural significance. They are a reminder of the joys and rewards of boundary-crossing, collaborative, shared, curious, and free-spirited creation.

The possibility and reality of their presence (and that of many of their peers) in Kenya’s, East and Central Africa’s, and the continent’s musical history at large is proof that musical success and evolution is achievable right here, at home. It’s a history lesson in this success, and an exciting reminder of how much further local art can go if it is culturally authentic and community driven.

Orchestra Super Mazembe was a daring project. It was ambitious, a great risk. It was joy and obsession and dedication to African art and creation, regardless of barriers. It was a need to connect, to tell stories beyond themselves, even when that meant that they had to learn to communicate in other ways or words or sounds to do so. It would’ve been too big a dare to some, maybe, and yet they did it; inspiring different generations of artists and consumers alike, and offering a reminder that connection and understanding are possible, if you just dare.

What’s more heroic than that?