artist-on-artist

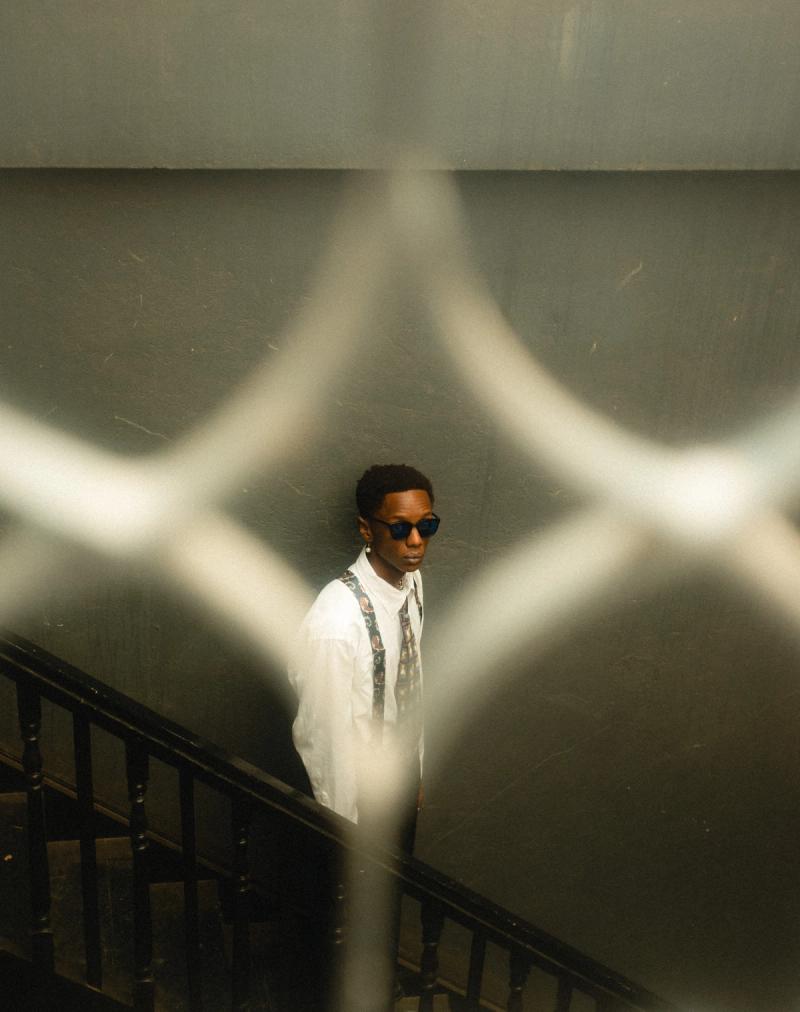

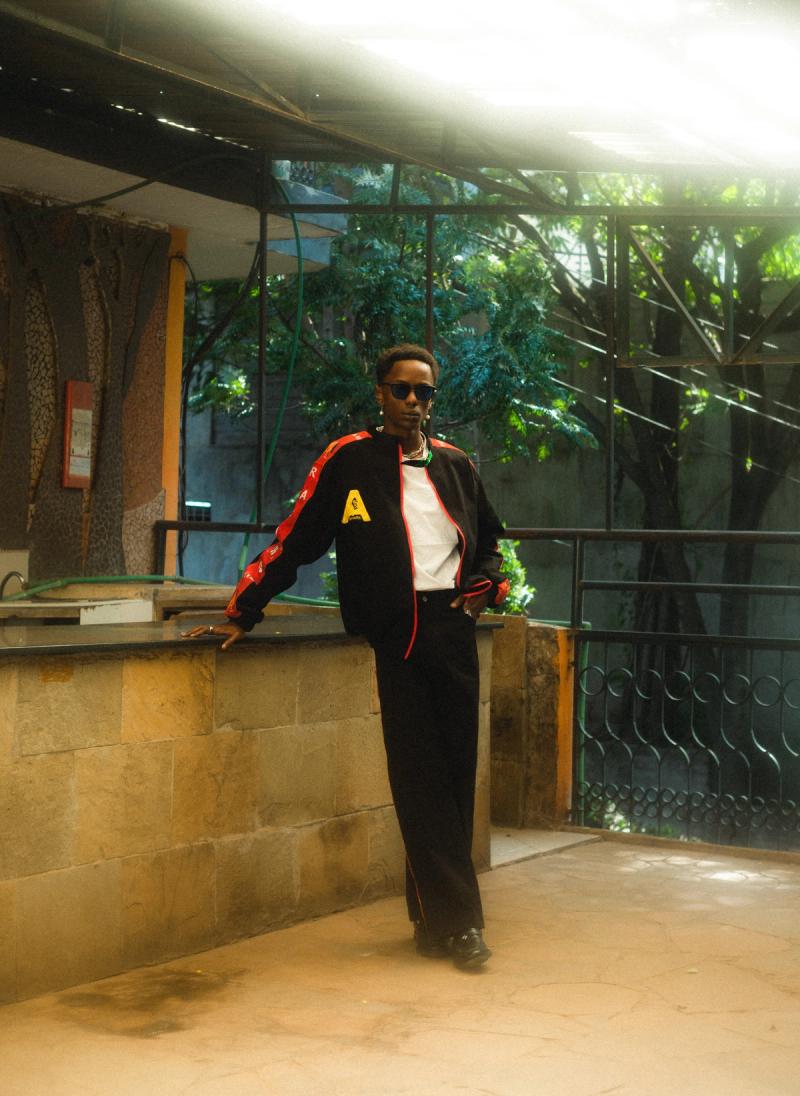

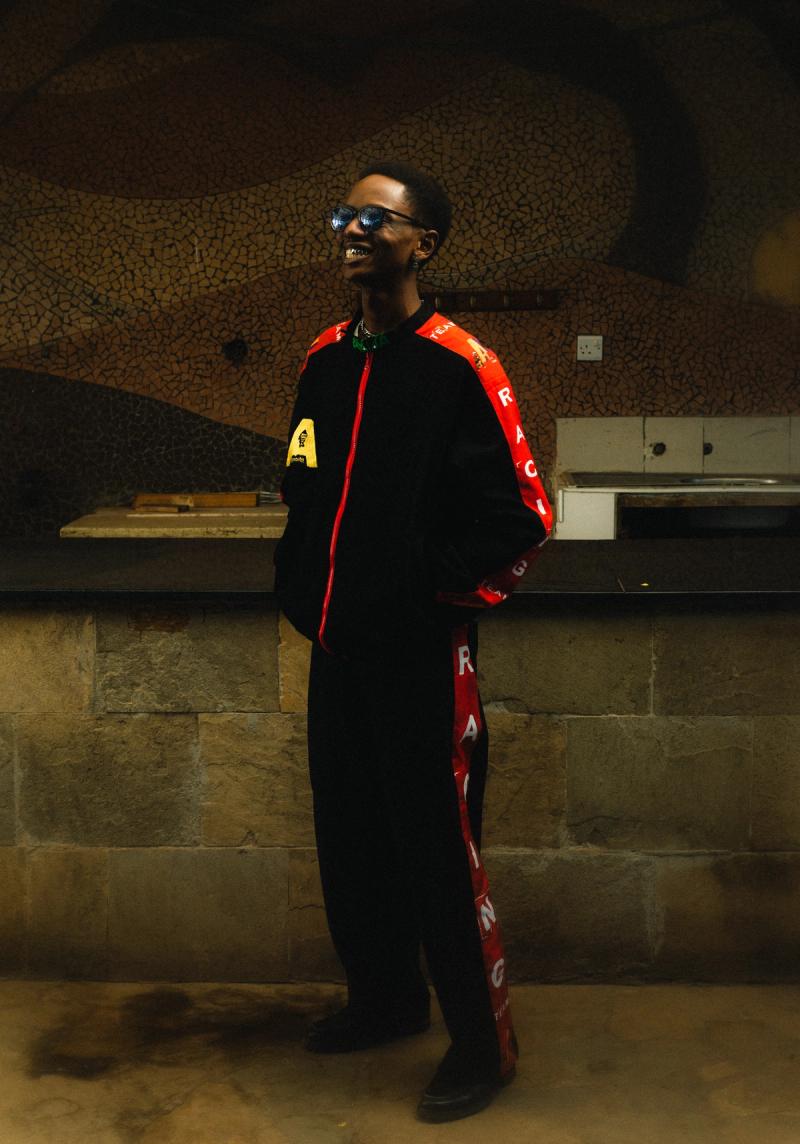

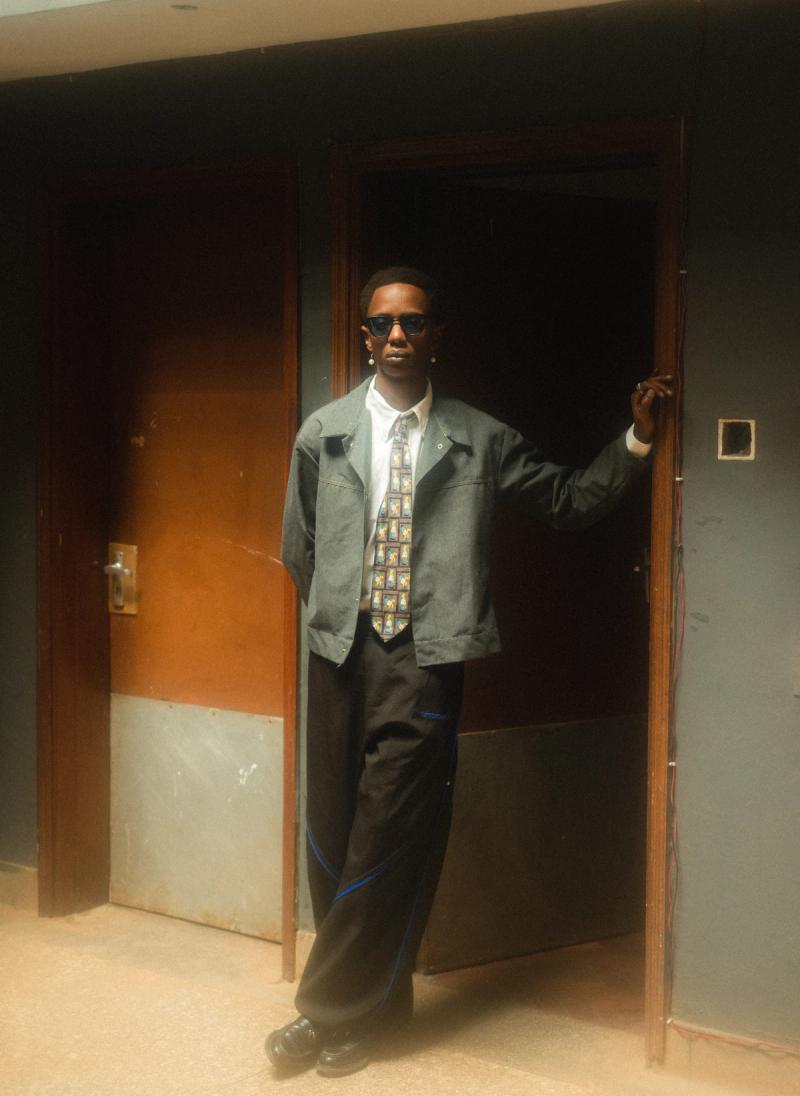

Artist x Artist: mwami x KYmani

by Franscine Machinda

March 13, 2025

artist-on-artist

March 13, 2025

mwami and KYmani are out of the ordinary – and I don’t mean extraordinary. I mean that their talents are almost too severe to be considered as just more than something that already exists in East Africa’s artistic landscape.

mwami’s depth goes beyond the pitch of his voice as he pulls you into the 'olympean' universe with poetic prose delivered almost casually, swinging smoothly from the smug playfulness of boy scout to the tenderness of daisy. In 'EA OPEN', his border-crossing project with Tai Dai and Agent Mgumbe, he reinforces this versatility, effortlessly going from casual-hookup-voice-note in SOIRÉE to earnest “overly passionate” 2am phone call in FLEVA.

On the other hand, KYmani’s world is one I can only describe as transcendental while mwami describes it as a “visceral memory”. It’s glowy and distant even in its precision, existing in a plane where time seems meaningless and perception of reality useless. It’s what I’d imagine astral projection feels like.

There’s a care in how both these artists work, a tenderness in how they present the work, and a softness in how they talk about the work. They are the perfect pair really, and so in our second ‘Artist x Artist’ feature, I got to be a fly on the wall as they discussed heritage, aloneness, and what it means to explore yourself through your art.

***

KYmani: How have you been since the last time we met?

mwami: Oh man, it's been hectic. But it's been good. I've had a chance to look at your work. We can start at what is a beginning of sorts. How did you get into it? And then I can maybe ask specific questions as to the evolution of this, because I was noticing a couple of interesting things the further back I went, and maybe for those questions to make sense, we can start from the beginning. Tell me a little bit about your journey with the visual medium and how you arrived at this point.

KYmani: My journey was a bit accidental. Initially, I didn't know anything about photography as an art form. Before, my perception of photography was just the family pictures and that kind of stuff. I guess that’s because I wasn't on social media even though most of my friends were. After I finished high school, somehow I was in Sunday school and one of my teachers had a camera he used to take pictures of church events. One day, he gave me the camera to hold onto for him. I started playing around with it, just pressing buttons, and I took a photo of my friend, which he liked so much that he suggested I look into photography.

He introduced me to someone with a camera we could rent from, so we decided to have a photoshoot and see how it goes. For that first one, we went to Central Park which was the prime location for shoots during that time. We initially had a few friends we were planning to shoot, and we were depending on them to be able to pay for the camera and our transportation. So we wait And we wait and wait. Then they start calling, oh, bro, I'm sorry, I can't make it. And now I have a camera that I don't have the money to pay for. I don't know anything about anything. It was very, very stressful. Luckily, there was another group that just came randomly to Central Park, and I don't know what happened to their photographer, but we approached them and were able to avert the crisis.

That was the first time. From then on, it was a matter of the usual; on Sundays we’d organize a shoot, but this time at least you're sure that people will come. And then we go on and go on and go on. And I guess that's how now I found my way into photography. Eventually, I started linking with people who are also practicing photography as an art form, like a homie of mine called Kibe Nduni and Nala, who I now work with.

mwami: The further I went into your work, the more I could sense and see some elements that were very consistent maybe five to seven years ago; there was a wave of street photography in Kenya and East Africa. It was like a visual language of sorts, a certain kind of dreamy, ever slightly surreal type of editing, but in a very documentary type of way – whether it's people on the street or nature. I almost get this sense that your work didn't develop in a vacuum, that there was a community of people that you were either shooting with, working with, exchanging ideas, exchanging tools, exchanging processes. And it seems to be what you're saying, where you would shoot with people, you’d source equipment with people, there was this collective approach that I imagine created a cohesive visual language. I'm now so curious as to how you got to a point where you want to develop your own voice and certain things about your approach and style that maybe become particular to you.

When we were shooting the other day, there were techniques that are practical, they're pragmatic, whether it's applying substance or adhesives to the lenses to get a certain feel, the choice of the lenses that you use. I'm curious as to how you then began to find and almost just refine what is your style and approach out of the community that you had come into the medium with?

KYmani: Just today I saw a word – geidō. It's a Japanese phrase that describes the creative process. You start with commitment, just like how despite all the stuff that was going on, despite not making money and almost being arrested and all that, I still had that commitment in trying to see where photography can lead me. The next is imitation and mimicry. That was me trying to copy what was happening. Now I've seen Nairobi photographers, I've seen these great photographers who've been doing this for a while, I want to see if I can match what they are doing because I really enjoy the aesthetics. My photography wasn't mentored. And that I had stumbled upon it accidentally and without any guidance, I might as well try and do it like these people.

Then the last one is expression, expressionism. Now that I already know the skills, I already know how to work my way around a camera, how can I push it? How can I experiment with what I have? And I guess that's where I'm at. At this point, I want to try anything. That's even why when we were shooting, of course, you saw the technique (applying petroleum jelly to the lens to create a dreamy effect). That is a very shitty technique. There's a proper way of doing it, where you get an expensive filter and you put it on top of a lens. But you might as well just use what you have. I don’t know if I’ve developed a visual style yet, of course there are some techniques I’ve developed recently, but I don’t think I have a complete style yet.

mwami: Aside from your peers, what would you say are your influences at large? Similar to the Japanese word, are there any processes or philosophies that have guided you so far?

KYmani: My current approach is absorption. I want to absorb as much as I can, across art forms. Even from music. When I first found your music, it felt to me like you were pushing the boundaries while doing what feels right to you. Those are the principles I’m trying to follow. I’ve also been watching a lot of African films and think there’s so much to borrow from African art in general. I currently work in a very procedural manner, so I am also looking forward to feeling a sense of freedom while creating.

I am deeply inspired by filmmakers, and I'm currently working on a film. I appreciate Ousman Sembene and Djibril Diop Mambety from Senegal, Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese from South Africa, Aleruchi Kinika and Adaeze Okaro from Nigeria, and Ingmar Bergman from Sweden.

The first time I came across your work was because of a book you made. I didn’t initially know that you were a musician. I was very intrigued because there was so much mystery around the book. Could you tell me about that? And your influences?

mwami: Creating larger bodies of work feels like a window of time – a season or an era – where the influences and the things ideas are being drawn from and the ideas I have this urge to explore are not just one dimensional or one art form. There was a point in time when I was done making music for protean but I wasn’t done with all ideas, that’s how the graphic novel came to be. There was poetry, photography, conversations, an idea for a comic, etc. It then all fell in line and in conversation with a body of work. With olympean, I began the visuals before finishing the music, and some of the visuals then influenced the music. All the ideas exist in one world of sorts and it might come to pass in different mediums and physical forms which I’m also very big on. This maybe comes from getting music in CD format or having to download your music into a flash when I was younger. Having a physical copy of something is unmatched. Then there's this idea of home, that someone who is a big fan of my work or of the people I work with can have their space populated with physical art and forms of expression from our community and bearing East African culture. Whether that be books, physical music, furniture, clothing, artwork; just this notion of an East African individual whose life is colored, informed, and populated with this culture in a physical way. So even with the film, I want to get to a point where I make some sort of DVD or any physical format that someone can collect and keep in some way.

In regards to influences, I would have to say Riky Rick. That's the most impactful as far as personal style. He's the first African artist that I interacted with who was existing across a few mediums in a way that was wholly unique and authentic. His approach to visual storytelling was unmatched. There's videos from 10 years ago that look like they came out today. You don't do that kind of thing by mistake, you have to set out with a very strong vision. So above all other influences, because of course there is a long list of others, that would be a main one.

What's been your experience with art forms and mediums other than photography? Have you explored other elements? Maybe auditory art, how have you interacted with that?

KYmani: I listen to so much music. There's been so much contemporary African music coming up. I recently found this experimental Kenyan/German duo called ODD OKODDO. Their work is very experimental, and that collaboration is inspiring. This year I want to do as many intentional and impactful collaborations as possible. I happen to know a lot of artists and it's interesting to see how we can come together and make something.

Franscine: Jumping in because I'm quite curious about something specific. As a writer, I sometimes consider myself an artist, sometimes not. Either way, writing is quite a solitary experience. There's a certain…I don't want to say loneliness, so I’ll say a certain aloneness that comes with writing. Then when I put it out there, I have no idea who's reading it, who's responding, or how they're reacting to it. So it’s a bit jarring every time I meet someone that's read something I wrote, especially because I write a lot of personal essays. It's kind of crazy to talk to strangers about emotionally charged experiences I wrote about when they don’t really know me, even though they know about the experiences. And I find that in situations like that, I tend to become a different person. I have this filter of protection, maybe, that allows me to detach myself from the work in order to present it.

I've seen both of you work and interacted with you casually when you’re not working, and I think both of you turn into different people when working too. Do you do that consciously, or is it just that you're absorbed in the creative process and in that particular time you're nothing but an artist and the art is all that matters? Is that you creating this world that only belongs to you even though we are witnessing it? And the aloneness? Do you ever feel like that when working?

mwami: Aloneness, yes. I think the work is very isolated for the longest time, in the sense that it often exists in a small space for what is a pivotal part of the process, which is just in my phone or in the possession of one to two people. But there's something freeing in that aloneness. It's what allows for the exploration of different facets of myself, different dimensions of personality, which is what can then be interpreted as an alternative or this other person that often people experience in a live setting, which has been mentioned before. You put it in a very apt way. The result of what occurs in that aloneness in a safe and artistically volatile and experimental space allows for, and this live context is like a window into that, seeing one facet of what that looks like brought forth in a shared space.

It's not really removed from myself or created in a designed way. It's just more so, I would say it's like the internal equivalent of there being a dress code. There's a code of conduct that now is appropriate here that maybe in my daily life is not as appropriate. I can wear these clothes as far as my personality or my internal makeup is concerned in this context. And doing so in every other context would almost feel inappropriate, it would feel a bit like I'm not “dressed for the occasion.”

KYmani: For the longest time it felt like I was just creating for myself and then people would just see. I’d have this idea in my head that would be killing me. Then I’d start looking for resources or things or people to collaborate with, and then we’d create and I’d showcase it for my own sake. It's both good and bad, because I realize I'm a very harsh critic of myself. I think there's a whole year where I didn't even want to showcase anything. And this is just on Instagram. I am still thinking of doing a physical, I remember even mwami talking about the physical art form, and that's something that I really take seriously. I'm still trying to see if I can force myself to think that I have any work that is good enough to showcase physically. So that's where I'm at.

When it comes to a persona, I don't think I have one. When I’m creating, it’s a zone, and you feel like nothing else matters other than what you're trying to achieve or create. I’ve been realizing this, especially now with the stuff that I'm trying to work on, like I've been drawing. There's a project that I started, which is just a drawing project, and it has taken me a while, but I'm still doing it.

This is a new art form, not new per se, but it's new to me and it's very difficult. It's called 12 Pastels and it's really, I'm really struggling with it, but it's kind of refreshing any time something comes out of it. I guess in those times you can say, from an outer perspective you might think I'm a different person because I'm too locked in. But personally, I don't think I have any personas when it comes to creating. I like being fully present when I'm creating. I don't have to take this other personification for me to create this work. I want to feel like I'm fully, fully there. The only time I allow myself to be somebody else is when I'm alone, like when I'm trying to edit or draw when alone. But when I'm in the presence of people, especially, I would like to be fully present.

Franscine: Yeah, I think context and the art form are quite important.

Do you ever feel like the work is done? The alternative to that question would be, when is the work done? And the answer would be never. But how do you know when to stop? When do you realize that you have to stop touching it in the hope of pushing it further or you’ll destroy it?

Kymani: I don't think art is ever done, because if it was done then neither of us would be doing it right now. Of course, there's times where you can say that a particular project is done, but in the general sense I don't think it ever is, because we keep trying to improve, trying to come up with something different, trying to experiment.

For example, if I have a project in mind that I'm executing, if you hear a photographer say, one more, it means you're doing like 50 more shots, because there's that feeling that you still have something to improve, something else you can achieve, you keep seeing something different every time you look into the camera or the person changes something or the lighting changes, it feels like it cannot stop, it feels like it's not done. There's an importance in knowing when you wanna call it done. When you wanna be like, okay, I think this is enough. I think this is all right. And I think having that in mind before creating is important. It allows you to be focused on what you want to achieve. That's my definition of done.

mwami: For me, it's a sliding scale. The right answer, in theory, is that if there's nothing left that I can take away or change or add, then it's done. Even if the feelings around that are unresolved, that's just sort of the end point; that there's no other element that can be taken away to reduce this to its most pointed and concise, and adding anything will not in any shape or form make it better or get the idea across in a clearer way. And that's not a precise place. It's a very distinctive thing, and some of it is also trial and error and sitting with it a little bit to definitively know that.

There's been points where something was done long before I was ready to accept it, and I just needed the time to try this and have it not work and then take this away and realize that that piece was actually pivotal – that kind of trial and error and then just come to terms with it. There are good backstops or fail safes or people who I can rely on to help put that point into perspective. But most times, really, truly, only you – the person, the creator, whatever it is – ultimately know. But yes, the work being done and you being ready to accept that it's done are two separate things. And I suppose the latter is more important, because without being in a position of acceptance that this is done, I don't think you can release anything. Even if the work is perfect, whatever the case may be, until you're at that point, then it isn't really.

KYmani: We had roughly talked about making music across the borders, is it going to be an East African thing? Are you working with Tanzanians? Do you have that in mind? And what's it like making music across borders?

mwami: I think first of all, making music, making art can feel like a kind of alchemy, a kind of wizardry of sorts. It's coming across people, or a people, who just have a different spell book than you, and you're exchanging spells, you're exchanging technique, you're exchanging approach. It feels anamorphous in that way, where there's just secrets – not secrets, but things you're yet to uncover that by the virtue of learning it in a different place. Someone's just bound to have insights that you don't and vice versa. I would say the most practical or obvious or surface level difference is that I suppose, maybe just by population size, there's just a sheer, larger number of people with a technically, a professionally technical level operating in Kenya than they would be in Uganda. It's just an older market. It's just like a larger market. People have been doing it longer in larger numbers.

But at the same time, there is an experimentation with the local traditional music and sounds that's happening in Uganda that arises out of a creativity, from not knowing the way or not knowing what it is supposed to be that allows you to be very imaginative with how you solve problems.

What about you? Have you had any experience in working with artists beyond Kenya? And any real difference that you see in their work versus yours or in their context versus yours?

Kymani: No, it's been mostly here in Kenya. But I've realized that our country is huge, there's so much you can learn. At the moment, before I go beyond the borders and start exploring or working with other artists, I'm on this part where I'm trying to learn. I have just come to the realization that there's so much that I don't know about this place, about Kenya. And there's so many pockets of inspiration everywhere.

Two weeks ago, we went to a museum called Kikuyu Museum. I am Kikuyu, so it was very interesting for me to find this. Somebody decided to archive stuff from my local dialect. This is somebody who decided to collect things to have this information about where I'm coming from. Like, why am I speaking the way I'm speaking or why can I hear this language?

I've been on the journey of trying to rediscover myself through understanding where I'm at and where I'm from, even from an ancestral point of view. I even had the opportunity to know where my great grandma comes from and where my lineage starts from. I had some sort of insight from that. As I said, I'm trying to really consume, trying to rediscover, to receive this inspiration, because I feel like there's a lot of stuff to take inspiration from. And I think that will lead me to better understand myself. And then I'll try to work across borders, because I also want to see the approach that people are taking in their work out there.

mwami: You brought up a topic I wanted to touch on, which is lineage, if exploring archived material, old family relics, or memorabilia is in any way impactful to your style. I can see or sense this feeling of creating a visceral almost like a memory in some of your photography. It feels very nostalgic. It feels dreamy. I'm just curious if any of that was informed by any historical or personal lineage of sorts.

Kymani: I think me creating or having that kind of nostalgic feel is more of a longing and not an influence. I'm kind of longing to go back, to learn, to... I wasn’t directly inspired by lineage or any of that. It just happened. It just came to be. It was inherent. And now that I'm realizing it, I want to be very intentional with going back and looking at stuff because I've realized there's so much that is there that we don't even know is there. Like a good example, and it's kind of sad, when we went to this museum, we found out that the tribe that I'm from, the Kikuyu tribe, they had their own literature, their own way of communicating, their own way of writing things down. They used to have this instrument, which is called Gichande. It looks like a gourd. You put seeds from a specific tree in it, and then there's a way you shake it to communicate something specific. It's also decorated with some patterns and those patterns mean something. Everything was very intentional. There are very few people who knew how to communicate with that instrument, and most of those people are gone, and that's a lost art.

And from that point, there's so much that we don't know that we need to know, and I'm really trying to be very intentional in trying to see if there are other things in the culture, not even in just my own tribe or anything, just in the African culture. And when I want to go beyond the borders, I want to start from the very ancestral parts, not just the contemporary. Of course I respect the contemporary, but I want to try and see if I can uncover some of these deep underlying cultural norms or cultural artifacts that influence what you do today, because I think it's very important.

I'd like to also ask you, are there any discoveries that you've made in terms of your lineage that influences what you're doing today? And in your album, I think, was it Emerald? Yes. Is that also influenced by where you're coming from? And can you please talk to me more about that?

mwami: Yeah, very much so. Right from the beginning, the name mwami, while it was a name, it's a title or a term of endearment. It was given to me as a name by my late grandmother, and carrying that in my work is just that constant relation to that. Emeralda specifically, that's my mother's mother tongue, the language of my grandmother on that side. How do I start the story of Emeralda? Because it very much started with the video and the visual of olivine. There was just a lot of world and video and footage and coverage left over that we were able to then build story on top of. And then I wrote, well, Maxine, this incredible writer, she's a Ugandan poet, and she was gracious enough to build the initial body. And then I was able to translate that with Akeine and Bowman, who are Ugandan artists. So it was a holistic Ugandan effort in terms of the writing, the translation, the narration. And then it becomes further East African as Nyokabi comes in to add the score and the layer, just make it sonically richer. I always wanted these little details that in some shape or form added to the canon, so to speak, of these languages in a way that maybe they hadn't been used before, or at least in my experience and in my exposure. And that, I feel, adds to the language in a way, like where there is now media and artifacts that the language finds new forms for. And taking something that was spoken word and turning it into a visual piece, there's now a visual element to this that, again, adds further dimension to the language.

I was very much captivated by foreign film, how foreign film feels where you have to engage with this worldview beyond a language you can understand. It's being translated to you in some shape or form, but the visual language is something you almost have to translate for yourself in a way and decipher.

It's contextualized to a language that's very personal and intimate to me, one I don't necessarily even speak as such, but one that my mother and her family do. And it's a way to give back in a sense, to reconnect or to add value to something that is kind of responsible for how you got here. So that's my relation to lineage in a way. It's like a pointed recognition of the details and the nuances that led to me being able to do what I do or to be where I am.

KYmani: That’s very new information that I've gotten, thank you for that. What are you currently working on? What’s next after olympean?

mwami: Back to Franscine's question, if the work is ever really over, I want to do a deluxe edition of the album and a director’s cut of the film that I feel like is truly, truly done. And then beyond that, musically, I really wanted to do more collaborative projects. I did an EP called EA OPEN with Tai Dai and Agent Mgumbe and we're talking about doing a second one.

Then also there's these artists MAUIMØON, Kalibwani who are Ugandan writers, performers, and producers as well. With Agent Mgumbe, we make up what's a collective called Bugos Boys and we’re talking about doing a full-length project that's more so hip hop leaning and focused, getting more back to bars and writing in like a traditionally hip hop capacity. My personal music is very dance oriented. It's very product heavy. And these collaborative projects really allow for me to exist in a particular form. I'm either just a producer or just a writer. That restriction in a way brings out an element that can only exist in collaborative spaces, and I'm kind of keen on that now.

I feel like there's something quite exhausting about solo material. It takes a bit out of you. Because again, that aloneness that we've been talking about is ever so pronounced when you work in that way. But in collaborative contexts, it's kind of inverted. That aloneness is purely shared. And you create this short-form language as far as the how the ideas flow between you and how you translate them and how you inspire each other, it becomes very charged; and once there's momentum in that direction there's something about it. There was a moment in making EA OPEN that felt like a hive mind, like the three of us were not in every session and in every creative decision or having to impart something, but there was this flow between us at every step Everyone's influence is felt and it's imparted in a very authentic and free-flowing way.

But what about you? What are you, what are you working on?

KYmani: I'm working on a photography project called RANGI RANGILE. I'm working with designers, but the main designer is called Sophie.

So I come up with an idea and it's centered around a certain color, but we don't really take the meaning of that color literally, but just take the color and it describes the shoot of the set and the design. And the other project is now working on a film. I'm working with different writers and trying to collect material from everywhere.

I guess that's where I'm at right now. And it's very, very interesting.

All pictures of mwami courtesy of KYmani.